Dr. O. Aly

Computer Science

Introduction

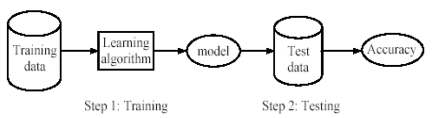

The purpose of this discussion is to discuss how the Logistic Regression used to predict the categorical outcome. The discussion addresses the predictive power of categorical predictors of a binary outcome and whether the Logistic Regression should be used. The discussion begins with an overall overview of variable types, business analytics methods based on data types and by market sector. The discussion then addresses how Logistic Regression is used when working with categorical outcome variable, and it ends with an example of Logistic Regression using R.

Variables Types

Variables can be classified in various ways. Variables can be categorical or continuous (Ary, Jacobs, Sorensen, & Walker, 2013). When researchers classify subjects by sorting them into mutually exclusive groups, the attribute on which they base the classification is termed as a “categorical variables” (Ary et al., 2013). Examples of categorical variables are home language, county of residence, father’s principal occupation, and school in which enrolled (Ary et al., 2013). The simplest type of categorical variable has only two mutually exclusive classes and is called a “dichotomous variable” (Ary et al., 2013). Male-Female, Citizen-Alien, and Pass-Fail are examples of the dichotomous variables (Ary et al., 2013). Some categorical variables have more than two classes such as educational level, religious affiliation, and state of birth (Ary et al., 2013). When the attribute has an “infinite” number of values with a range, it is a continuous variable (Ary et al., 2013). Examples of continuous variables include height, weight, age, and achievement test scores (Ary et al., 2013).

The most important classification of variables is by their use in the research under consideration when they are classified as independent variables or dependent variables (Ary et al., 2013). The independent variables are antecedent to dependent variables and are known or are hypothesized to influence the dependent variable which is the outcome (Ary et al., 2013). In experimental studies, the treatment is the independent variable, and the outcome is the dependent variable (Ary et al., 2013). In a non-experimental study, it is often more challenging to label variables as independent or dependent (Ary et al., 2013). The variable that inevitably precedes another one in time is called an independent variable (Ary et al., 2013). For instance, in a research study of the relationship between teacher experience and students’ achievement scores, teacher experience would be considered as the independent variable (Ary et al., 2013).

Business Analytics Methods Based on Variable Types

The data types play a significant role in the employment of the analytical method. As indicated in (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016), when the response (dependent) variable is continuous, and the predictor variables are either continuous or categorical, the Linear Regression, Neural Network, K-Nearest Neighbor (K-NN) methods can be used as detailed in Table 1. When the response (dependent) variable is categorical, and the predictor variables are either continuous or categorical, the Logistic Regression, K-NN, Neural Network, Decision/Classification Trees, Naïve Bayes can be used as detailed in Table 1.

Table-1: Business Analytics Methods Based on Data Types. Adapted from (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016).

Analytics Techniques/Methods Used By Market Sectors

In (EMC, 2015), the Analytic Techniques and Methods used are summarized in Table 2 by some of the Market Sectors. These are examples of the application of these analytic techniques and method used. As shown in Table 2, Logistic Regression can be used in Retail Business and Wireless Telecom industries. Additional methods are also used for different Market Sector as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Analytic Techniques/Methods Used by Market Sector (EMC, 2015).

Besides the above Market Sectors, Logistic Regression can also be used in Medical, Finance, Marketing and Engineering (EMC, 2015), while the Linear Regression can be used in Real Estate, Demand Forecasting, and Medical (EMC, 2015).

Predicting Categorical Outcomes Using Logistic Regression

The Logistic Regression model was first introduced by Berkson (Colesca, 2009; Wilson & Lorenz, 2015), who showed how the model could be fitted using iteratively reweighted least squares (Colesca, 2009). Logistic Regression is widely used (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014; Colesca, 2009) in social science research because many studies involve binary response variable (Colesca, 2009). Thus, in Logistic Regression, the target outcome is “binary,” such as YES or NO or the target outcome is categorical with just a few categories (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014), while the Regular Linear Regression is used to model continuous target variables (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014). Logistic Regression calculates the probability of the outcome occurring, rather than predicting the outcome corresponding to a given set of predictors (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014). The Logistic Regression can answer questions such as: “What is the probability that an applicant will default on a loan?” while the Linear Regression can answer questions such as “What is a person’s expected income?” (EMC, 2015). The Logistic Regression is based on the logistic function f(y), as shown in equation (1) (EMC, 2015).

The expected value of the target variable from a Logistic Regression is between 0 and 1 and can be interpreted as a “likelihood” (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014). When y à¥, f(y) à1, and when y à–¥, f(y) à0. Figure 1 illustrates an example of the value of the logistic function f(y) varies from 0 to 1 as y increases using the Logistic Regression method (EMC, 2015).

Figure 1. Logistic Function (EMC, 2015).

Because the range of f(y) is (0,1), the logistic function appears to be an appropriate function to model the probability of a particular outcome occurring (EMC, 2015). As the value of the (y) increases, the probability of the outcome occurring increases (EMC, 2015). In any proposed model, (y) needs to be a function of the input variables in any proposed model to predict the likelihood of an outcome (EMC, 2015). In the Logistic Regression, the (y) is expressed as a linear function of the input variables (EMC, 2015). The formula of the Logistic Regression is shown in equation (2) below, which is similar to the Linear Regression equation (EMC, 2015). However, one difference is that the values of (y) are not directly observed, only the value of f(y) regarding success or failure, typically expressed as 1 or 0 respectively is observed (EMC, 2015).

Based on the input variables of x1, x2, …, xp-1, the probability of an event is shown in equation (3) below (EMC, 2015).

Using the (p) to denote f(y), the equation can be re-written as shown in equation (4) (EMC, 2015). The quantity ln(p/p-1), in the equation (4) is known as the log odds ratio, or the logit of (p) (EMC, 2015).

The probability is a continuous measurement, but because it is a constrained measurement, and it is bounded by 0 and 1, it cannot be measured using the Regular Linear Regression (Fischetti, 2015), because one of the assumptions in Regular Linear Regression is that all predictor variables must be “quantitative” or “categorical,” and the outcome variables must be “quantitative,” “continuous” and “unbounded” (Field, 2013). The “quantitative” indicates that they should be measured at the interval level, and the “unbounded” indicates that there should be no constraints on the variability of the outcome (Field, 2013). In the Regular Linear Regression, the outcome is below 0 and above 1 (Fischetti, 2015).

The logistic function can be applied to the outcome of a Linear Regression to constrain it to be between 0 and 1, and it can be interpreted as a proper probability (Fischetti, 2015). As shown in Figure 1, the outcome of the logistic function is always between 0 and 1. Thus, the Linear Regression can be adapted to output probabilities (Fischetti, 2015). However, the function which can be applied to the linear combination of predictors is called “inverse link function,” while the function that transforms the dependent variable into a value that can be modeled using linear regression is just called “link function” (Fischetti, 2015). In the Logistic Regression, the “link function” is called “logit function” (Fischetti, 2015). The transformation logit (p) is used in Logistic Regression with the letter (p) to represent the probability of success (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014). The logit (p) is a non-linear transformation, and Logistic Regression is a type of non-linear regression (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe & Coleman, 2014).

There are two problems that must be considered when dealing with Logistic Regressions. The first problem is that the ordinary least squares of the Regular Linear Regression to solve for the coefficients cannot be used because the link function is non-linear (Fischetti, 2015). Most statistical software solves this problem by using a technique called Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) instead (Fischetti, 2015). Techniques such as MLE are used to estimate the model parameters (EMC, 2015). The MLE determines the values of the model parameters which maximize the chances of observing the given dataset (EMC, 2015).

The second problem is that Linear Regression assumes that the error distribution is normally distributed (Fischetti, 2015). Logistic Regression models the error distribution as a “Bernoulli” distribution or a “binomial distribution” (Fischetti, 2015). In the Logistic Regression, the link function and error distributions are the logits and binomial respectively. In the Regular Linear Regression, the link function is the identity function, which returns its argument unchanged, and the error distribution is the normal distribution (Fischetti, 2015).

Logistic Regression in R

The function glm() is used in R to perform Logistic Regression. The error distribution and link function will be specified in the “family” argument. The family argument can be family=”binomial” or family=binomial(). Example of the glm() using the births.df dataset. In this example, we are building Logistic Regression using all available predictor variables on SEX gender (male, female).

References

Ahlemeyer-Stubbe, A., & Coleman, S. (2014). A practical guide to data mining for business and industry: John Wiley & Sons.

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., Sorensen, C. K., & Walker, D. (2013). Introduction to research in education: Cengage Learning.

Colesca, S. E. (2009). Increasing e-trust: A solution to minimize risk in e-government adoption. Journal of applied quantitative methods, 4(1), 31-44.

EMC. (2015). Data Science and Big Data Analytics: Discovering, Analyzing, Visualizing and Presenting Data. (1st ed.): Wiley.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics: Sage publications.

Fischetti, T. (2015). Data Analysis with R: Packt Publishing Ltd.

Hodeghatta, U. R., & Nayak, U. (2016). Business Analytics Using R-A Practical Approach: Springer.

Wilson, J. R., & Lorenz, K. A. (2015). Short History of the Logistic Regression Model Modeling Binary Correlated Responses using SAS, SPSS and R (pp. 17-23): Springer.