Dr. O. Aly

Computer Science

Abstract

The purpose of this project is to analyze the German Credit dataset. The project is divided into two main Parts. Part-I evaluates and examines the DataSet for understanding the Dataset using the RStudio. Part-I involves six significant tasks. Part-II discusses the Pre-Data Analysis, by converting the Dataset to Data Frame, involving four significant tasks to analyze the Data Frames. Although the project analyzes three significant models including Standards Linear Regression, Multiple Linear Regression, the Logistic Regression is the emphasis of this project. The result shows that the duration, amount, installment and rent show positive coefficient values indicating that they have a positive impact on the probability of the dependent binary outcome (Default). As the p-value is much less than 0.05 for duration, amount, installment, history, purpose for used car, goods, repair, and business, and rent, we reject the null hypotheses that there is no significance of the parameter to the model and accept the alternate hypotheses that there is significance of the parameter to the model. The p-value for the age is (p=0.05) indicating that we accept the null hypothesis that there is no significance of the parameter to the model. The p-value for (purpose) of education is > 0.05 indicating that we accept the null hypothesis that there is no significance of the parameter to the model. The performance of the Logistic Regression model for the test dataset shows that the Logistic Regression recognizes 23 of the 28 Defaults (82%) and predicts the defaults 42 of the 72 good loans (58%).

Keywords:

German-Credit

Dataset; Regression; Logistic Regression Analysis Using R.

Introduction

This project examines and analyze the dataset of (german.credit.csv). The dataset is downloaded from the following archive site for machine learning repository:

https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Statlog+(German+Credit+Data).

The dataset has 1000 obeservation on 22 variables. There are two datasets for german.credit.csv. The original dataset, in the form provided by Professor Hofmann, contains categorical/symbolic attributes and is in the current german.credit.csv file which is used in this project. The other dataset “german.data-numeric” is not used in this project which was developed by Strathclyde University for algorithms that need numerical attributes. This project utilized the original version of german.credit.csv which has categorical variables, because these categorical variables will be transformed during the analysis process to generate various models including linear models, and logistic model.

There are two Parts for this project. Part-I addresses five tasks to examine and understand the dataset using R before the analysis as follows:

- Task-1: Review the Variables of the Dataset

- Task-2: Understand the Dataset using names(), head(), and dim() functions

- Task-3: Pre and Post Factor and Level of Categorical Variables of the Dataset.

- Task-4: Summary and Plot the Continuous Variables: Duration, Amount, and Installment

- Task-5: Classify Amount into Groups.

- Task-6: Summary of all selected variables.

Part-II address the analysis using R. Part-II includes seven tasks include the following. These seven tasks are followed by the discussion and analysis of the results.

- Task-1: Select and Plot Specific Variables for this Project.

- Task-2: Model-1: Linear Regression – single variable, and Diagnostic Analysis.

- Task-3: Model-3: Multiple Regression Analysis

- Task-4: Discussion and Analysis.

There is an assumption that, on average, lending into default is five times as costly as not lending to a good debtor (default=success=0, no default=failure=1). The default is defined as “success,” while no defaulting on a loan is defined as “failure.” If a certain (p) for the probability of default is estimated, the expected costs are 5p, assuming the bank makes the loan, and 1(1-p) if the bank refuses to make the loan. Thus, if 5p < 1-p, the bank can expect to lose less by making the loan than by turning away business. The following decision rule can be implied: make the loan if the probability of default p < 1/6. The prediction of Default (Success) is to implemented whenever p > 1/6.

This project analyuze the German Credit dataset. The two expected outcomes are success (defaulting on the loan), and failure (not defaulting on the loan). This project implements three models, Linear Regression, Multiple Linear Regression. However, the emphasis of this project is on the Logistic Regression (Model-3) to estimate the probability of default, using continuous variables (duration, amount, installment, age), and categorical variables (loan history, purpose, rent) as explanatory variables (independent variables).

Various resources were utilized to

develop the required code using R. These resources include (Ahlemeyer-Stubbe

& Coleman, 2014; Fischetti, Mayor, & Forte, 2017; Ledolter, 2013;

r-project.org, 2018).

Part-I: Understand and Examine the Dataset “german.credit.csv”

Task-1: Review the Variables of the Data Sets

The purpose of this task is to understand the variables of the dataset. The dataset is “german.credit” dataset. The dataset describes the clients who can default on a loan. There are selected variables out of the 22 variables which are target for this project. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize these selected variables for this project. Table 1 focuses on the variables with binary and numerical values, while Table 2 focuses on the variables with categorical values.

Table 1: Binary (Default) and Continuous (Numerical) Variables

Table 2: Categorical Variables.

Task-2: Load and Understand the Data Sets Using names(), head(), dim() functions.

The purpose of this task is to load and understand the data set using names(), head(), and dim() functions as shown in the code below.

- gc <- read.csv(“C:/CS871/german.credit.csv”)

- names(gc)

- head(gc)

- dim(gc)

- gc[1:3,]

Task-3: Pre and Post Factor and Level of Categorical Variables of the Data Sets

The purpose of this task is to factor and level all categorical variables and show the result pre- and post this process as shown in the code and snapshots below.

- ### history categorical variable pre and post factor and level.

- summary(gc$history)

- plot(gc$history, col=”green”, xlab=”History Categorical Variable Pre Factor and Level”)

- gc$history = factor(gc$history, levels=c(“A30”, “A31”, “A32”, “A33”, “A34”))

- levels(gc$history)=c(“good-others”, “good-thisBank”, “current-paid-duly”, “bad-delayed”, “critical”)

- summary(gc$history)

- plot(gc$history, col=”green”, xlab=”History Categorical Variable Post Factor and Level”)

Figure 1. Pre and Post Factor and Level of History Categorical Variable.

- ##### purpose pre and post factor and level

- summary(gc$purpose)

- plot(gc$purpose, col=”darkgreen”)

- ###tranform purpose

- gc$purpose <- factor(gc$purpose, levels=c(“A40″,”A41″,”A42″,”A43″,”A44″,”A45″,”A46″,”A48″,”A49″,”A410”))

- levels(gc$purpose) <- c(“newcar”,”usedcar”,”furniture/equipment”,”radio/television”,”domestic appliances”,”repairs”, “edu”,”vacation-doesNotExist”, “retraining”, “business”, “others”)

- summary(gc$purpose)

- plot(gc$purpose, col=”darkgreen”)

Figure 2. Pre and Post Factor and Level of Purpose Categorical Variable.

- ### housing categorical variable pre and post factor and level.

- summary(gc$housing)

- gc$rent <- factor(gc$housing==”A151″)

- summary(gc$rent)

- ##### housing categorical variable pre and post factor and level

- summary(gc$housing)

- plot(gc$housing, col=”orange”)

- gc$housing <- factor(gc$housing, levels=c(“A151”, “A152”, “A153”))

- levels(gc$housing) <- c(“rent”,”own”,”for free”)

- summary(gc$housing)

Figure 3. Pre and Post Factor and Level of Housing Categorical Variable.

Task-4: Summary & Plot the Numerical Variables: Duration, Amount, Installment, & Age.

The purpose of this task is to obtain the summary of the numerical variables: duration, amount, installment and age and plot the result.

- ##summary and plot of those numerical variables

- summary(gc$duration)

Figure 4. Duration Plot as a Numerical and Continous Variable.

- summary(gc$amount)

- plot(gc$amount, col=”blue”, main=”Amount Numerical Variable”)

Figure 5. Amount Plot as a Numerical and Continous Variable.

- summary(gc$installment)

- plot(gc$installment, col=”blue”, main=”Installment Numerical Variable”)

Figure 6. Installment Plot as a Numerical and Continous Variable.

- summary(gc$age)

- plot(gc$age, col=”blue”, main=”Age Numerical Variable”)

Figure 7. Age Plot as a Numerical and Continous Variable.

Task-5: Classify the Amount into Groups

The purpose of this task is to classify the amount into groups as shown below.

- #### To classify the amount into groups

- gc$amount <-as.factor(ifelse(gc$amount <=2500, ‘0-2500′, ifelse(gc.df$amount<=5000,’2600-5000’, ‘5000+’)))

- summary(gc$amount)

Task-6: Summary of all variables

The purpose of this task is to obtain the result of all required variables.

- summary(gc$duration)

- summary(gc$amount)

- summary(gc$installment)

- summary(gc$age)

- summary(gc$history)

- summary(gc$purpose)

- summary(gc$housing)

- summary(gc$rent)

Part-II: Plots, Discussion and Analysis

Task-1: Select and Plot specific variables for this project

The purpose of this task is to select the specific required variable and plot them into one single diagram.

- ##for demonstration, cut the dataset to these selected variables

- ##(duration, amount, installment, and age) which are numeric and

- ##(history, purpose and housing) which are categorical and

- ## Default (representing the risk) which is binary.

- gc.sv <- gc[,c(“Default”, “duration”, “amount”, “installment”, “age”, “history”, “purpose”, “foreign”, “housing”)]

- gc.sv[1:3,]

- summary(gc.sv)

- plot(gc.sv, col=”red”)

- ### Setting the Rent

- gc$rent <- factor(gc$housing==”A151″)

- summary(gc$rent)

Figure 8. Plot of all Selected Variables.

Task-2: Model-1: Linear Regression – single variable, and Diagnostic Analysis

The purpose of this task is to implement Model-1 for Linear Regression using one variable (History) as a factor for the Default.

- # to get a plot of the Default as dependent and history as independent

- plot(Default~history, data=gc, col=”darkred”)

- ##calculate the mean first – but no mean because of NA

- mean(gc$Default)

- # to check the NA values

- gc$Default

- ##we have to remove null values

- mean(gc$Default, na.rm=T)

- ##get the mean without NA values

- mean.Default=mean(gc$Default,na.rm=T)

- ## plot again after removing the NA value

- plot(Default~history, data=gc, col=”darkred”, main=”Default and History Effect”)

- #put horizontal line at the mean

- abline(h=mean.Default)

- #use lm to fit a regression line through these data:

- model1.Default.history = lm(Default ~ history, data=gc)

- model1.Default.history

- abline(model1.Default.history, col=”yellow”)

- plot(model1.Default.history)

- # to see the effect of solar

- termplot(model1.Default.history)

- #summary

- summary(model1.Default.history)

Figure 9. Model-1: Linear Regression Using the Mean Line (black).

Figure 10. Model-1: Linear Regression Using Regression Line (yellow).

Figure 11. Model-1: Four Diagnostic Plots For Standard Linear Regression.

Task-3: Model-2: Multiple Regressions Analysis

The purpose of this task is to implement Model-2 for Multiple Regressions including the Purpose, History, Installment, Housing, Amount, Duration, Age which can influence the Default as dependent variable.

- #Find relationship between multiple variables

- ##purpose on Default conditioned with history.

- coplot(Default~purpose|history, panel=panel.smooth, gc)

- ##rent on Default conditioned with history.

- coplot(Default~rent|history, panel=panel.smooth, gc)

- ##housing on Default conditioned with history.

- coplot(Default~housing|history, panel=panel.smooth, gc)

Figure 12. Model-2: Multiple Linear Regression Using Purpose, Housing, Rent, conditioned with History as factors influencing Default.

- ##amount on Default conditioned with duration.

- coplot(Default~amount|duration, panel=panel.smooth, gc)

- ##installment on Default conditioned with duration.

- coplot(Default~installment|duration, panel=panel.smooth, gc)

- ##age on Default conditioned with duration.

- coplot(Default~age|duration, panel=panel.smooth, gc)

Figure 13. Model-2: Multiple Linear Regression Using Amount, Duration as Factors influencing Default.

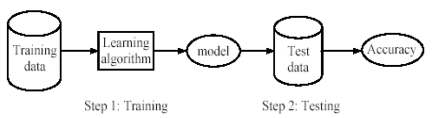

Task-3: Model-3: Logistic Regression Analysis

The purpose of this task is to implement the Logistic Regression Analysis.

- summary(gc)

- ###Create a Design Matrix

- ##Factor variables are turned into indicator variables

- ##The first column of ones is ommitted

- Xgc <- model.matrix(Default~.,data=gc)[,-1]

- Xgc[1:3,]

- ## Create training and prediction datasets

- ## Select 900 rows for estimation and 100 for testing

- set.seed(1)

- train <- sample(1:1000,900)

- xtrain <- Xgc[train,]

- xnew <- Xgc[-train,]

- ytrain <- gc$Default[train]

- ynew <- gc$Default[-train]

- gcglm=glm(Default~.,family=binomial,data=data.frame(Default=ytrain,xtrain))

- summary(gcglm)

- plot(gcglm, col=”blue”)

- coef(gcglm)

Figure 14. Model-3: Logistic Regression: Diagnostic Analysis: Residuals v. Fitted.

Figure 15. Model-3: Logistic Regression: Diagnostic Analysis: Normal Q-Q.

Figure 16. Model-3: Logistic Regression: Diagnostic Analysis: Scale-Location.

Figure 17. Model-3: Logistic Regression: Diagnostic Analysis: Residuals vs. Leverage.

- ## Now to prediction: what are the underlying default probabilities

- ## for cases in the test set

- ptest <- predict(gcglm, newdata=data.frame(xnew),type=”response”)

- data.frame(ynew,ptest)

- ## Using probability cutoff 1/6

- ## coding as 1 (predicting default) if probability 1/6 or larger

- probability.one.sixth=floor(ptest+(5/6))

- probability1=table(ynew,probability.one.sixth)

- probability1

- error=(probability1[1,2]+probability1[2,1])/100

- error

- ### Binary Classification, Using Probabiillties to make decision, sensitivity and specificity,

- ### Cut 1/6

- cut=1/6

- true.positive <- ynew==1 & ptest >= cut

- true.positive

- true.negative <- ynew==0 & ptest < cut

- true.negative

- # Sensitivity (predict default when it does happen)

- sum(true.positive)/sum(ynew==1)

- # Specificity (predict no default when it does not happen)

- sum(true.negative)/sum(ynew==0)

- ## Using probability cutoff 1/2

- ## coding as 1 if probability 1/2 or larger

- cut=1/2

- probability.half=floor(ptest+(1/2))

- probability2=table(ynew,probability.half)

- probability2

- error=(probability2[1,2]+probability2[2,1])/100

- error

- true.positive <- ynew==1 & ptest >=cut

- true.negative <- ynew==0 & ptest < cut

- # Sensitivity (predict default when it does happen)

- sum(true.positive)/sum(ynew==1)

- # Specificity (predict no default when it does not happen)

- sum(true.negative)/sum(ynew==0)

- ## R macro for plotting the ROC curve

- ## plot the ROC curve for classification of y with p

- roc <- function(p,y){

- y <- factor(y)

- n <- length(p)

- p <- as.vector(p)

- Q <- p > matrix(rep(seq(0,1,length=500),n),ncol=500,byrow=TRUE)

- fp <- colSums((y==levels(y)[1])*Q)/sum(y==levels(y)[1])

- tp <- colSums((y==levels(y)[2])*Q)/sum(y==levels(y)[2])

- plot(fp, tp, xlab=”1-Specificity”, ylab=”Sensitivity”)

- abline(a=0,b=1,lty=2,col=8)

- }

- ###### ROC for hold-out period

- roc(p=ptest,y=ynew)

- ## ROC for all cases (in-sample)

- gcglmall <- glm(gc$Default ~ Xgc,family=binomial)

- roc(p=gcglmall$fitted, y=gcglmall$y)

- ## using the ROCR package to graph the ROC curves

- library(ROCR)

Figure 18. Model-3: Logistic Regression: Sensitivity and Specificity for a sample of the data.

Figure 19. Model-3: Logistic Regression: Sensitivity and Specificity for All the data.

- ## input is a data frame consisting of two columns

- ## predictions in first column and actual outcomes in the second

- ## ROC for hold-out period

- predictions=ptest

- labels=ynew

- data=data.frame(predictions,labels)

- data

- ## prediction1: function to create prediction objects

- prediction1 <- prediction(data$predictions,data$labels)

- prediction1

- ## perf: creates the input to be plotted

- ## sensitivity and one minus specificity (the false positive rate)

- performance <- performance(prediction1, “sens”, “fpr”)

- performance

- plot(performance)

Figure 20. Model-3: Logistic Regression: ROC for specifc cases.

- ## ROC for all cases (in-sample)

- gcglmall <- glm(gc$Default ~ Xgc,family=binomial)

- predictions=gcglmall$fitted

- labels=gcglmall$y

- data=data.frame(predictions,labels)

- prediction2 <- prediction(data$predictions,data$labels)

- performance2 <- performance(prediction2, “sens”, “fpr”)

- plot(performance2)

Figure 21. Model-3: Logistic Regression: ROC for all cases.

Task-4: Discussion and Analysis

The descriptive analysis of the history (Figure 1) shows that the existing credits paid back duly till now are ranked number one of 530, followed by the critical account of 293, followed by the category of delay in paying off in the past of 88. The category of all credits at this bank paid back duly include only 49 and no credits taken or all credits paid back duly has only 40. The descriptive analysis of the purpose (Figure 2) shows that the radio/TV of 280 ranks number one in the loan, followed by the new car category of 234, followed by the furniture/equipment of 181, and used car of103. The business and education have 97 and 50 respectively, while the repairs, appliances, retaining and others have the least rank for loans. The descriptive analysis of the housing (Figure 3) shows that the own (Own=713) ranks number one for those who receive loans, followed by the rent (Rent=179). The category of “free” housing (Free=108) ranks the last for receiving loans. The descriptive analysis of the duration (Figure 4) shows that the duration average (Mean=21) is higher than the Median duration in a month (Median=18), indicating a positively skewed distribution. The maximum duration has the value of 72 months, while the minimum duration for the loan is four months. Most of the duration periods are up to 60 months. There is an outlier of the duration period of ~70 months as illustrated in Figure 4. The descriptive analysis of the amount (Figure 5) shows that the average amount of the loan (Mean=3271), is higher than the Median amount of the loan (Median=2320) indicating a positively skewed distribution. The maximum amount for a loan is 18424, while the minimum amount is 250. Most loans have the amount of ~5000, followed by the amount of 10,000-15,000. There is an outlier of a loan amount above 15,000 as illustrated in Figure 5. The descriptive analysis of the installment (Figure 6) shows that average installment (Mean=2.98) is higher than the Median installment (Median=1.00) indicating a positively skewed distribution. The maximum installment rate is 4.00, while the minimum installment has a rate of 1.00. The installment rates as illustrated in (Figure 6) are categorized between 1.00, 2.00, 3.00 and 4.00. The descriptive analysis of the age (Figure 7) shows that the average age (Mean=36) which is higher than the Median age (Median=33) indicating a positively skewed distribution. The maximum age is 75, while the minimum age is 19. As illustrated in Figure 7, most of the age is from ~20 to 50, with few densities from 50 to 60 and the fewest density is above 60 and 70.

The Linear Regression is the first model (Model-1) is implemented on the (history) explanatory variable over the default. The mean (Mean=3) is plotted in Figure 9 of the Linear Regression of history over the default. Another line is plotted in Figure 10 is illustrated the Linear Regression using the Regression Line. The result shows that there is a negative relationship between the Default (success) and the history. The bad history shows the success in defaulting on a loan. The diagnostic plots of the standard regression are also discussed in this project. Figure 11 illustrates four different diagnostic plots of the standard regression. This analysis also covers the residuals and fitted lines. Figure 11 illustrated the Residuals vs. Fitted in Linear Regression Model for the History explanatory variable as a function of the Default. The residuals depict the difference between the actual value of the response variable and the response variable predicted using the regression equation (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). The principle behind the regression line and the regression equation is to reduce the error or this difference (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). The expectation is that the median value should be near zero (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). For the model to pass the test of linearity, no pattern in the distribution of the residuals should exist (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). Where there is no pattern in the distribution of the residuals, it passes the condition of linearity (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). The plot of the fitted values against the residuals with the line shows the relationship between the two. The horizontal and straight line indicates that the “average residual” for all “fitted values” it is more or less the same (Navarro, 2015). The result of the Linear Regression for the identified variables of History and Default shows that the residual has a curved pattern, indicating that a better model can be obtained using the quadratic term because ideally, this line should be a straight horizontal line. Figure 11 also illustrates the Normal QQ plot, which is used to test the normality of the distribution (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). The residuals are not on the straight line, indicating that the residuals are not normally distributed. Hence, the normality test of the residuals did not pass, as it is supposed to be a straight line for the residuals to pass. Figure 11 also illustrates the Scale-Location graph, which is one of the graphs generated as part of the plot. The points are spread in a random fashion around the horizontal line but not equally the line. If the horizontal line with equally randomly spread points, the result could indicate that the assumption of constant variance of the errors or homoscedasticity is fulfilled (Hodeghatta & Nayak, 2016). Thus, it is not fulfilled in this case. Figure 11 also illustrates the Residuals vs. Leverage Plot generated for the Linear Regression Model. In this plot of Residuals vs. Leverage, the patterns are not as relevant as the case with the diagnostics plot of the Linear Regression. In this plot, the outlying values at the upper right corner or the lower right are watched (Bommae, 2015). Those spots are the places where a case can be influential against a regression line (Bommae, 2015). When cases are outside of the Cook’s distance, meaning they have high Cook’s distance scores, the cases are influential to the regression results (Bommae, 2015). The Cook’s distance lines are (red dashed line) are far indicating there is no influential case.

The Multiple Linear Regression is the second Model. Multiple variables such as purpose conditioned with history, rent conditioned with history, housing conditioned with history are used to implement the Multiple Regression models. There are two most noticeable results (Figure 12). The first noticeable result shows that the category of “good to other banks” that the default as success goes down when the loans are made for (purpose) of new car, furniture, radio/TV, domestic appliances, and repair, while the default as success goes up – meaning failure to default) with education, retraining, business and others. The second noticeable result is illustrated in the category of “currently paid duly,” that the default as success goes down meaning the loan receiver default on the loan when the loan is made to the same categories as the first noticeable result, but until radio/TV, after which the default on loan will fail for (purpose) of domestic appliances, repair, education, retraining, business, and others. The other Multiple Regression used the rent and free, the history shows a failure to default for the “good to others” category, while the own category shows success to default for the “current paid duly” category. For the rent specific, the result shows that these specific categories, there no default on loan with the rent on both categories. For the amount, installment and age conditioned with duration Multiple Regression models, the result shows that the loan 5000+, when the duration increases, the default failure increases, and when the duration decreases, the default failure decreases meaning there is a significant chance for defaulting on the loan. The same pattern shows when the installment increases, the default on a loan decreases. The same pattern is also shown for the age, when the age increases, the default on the loan decreases.

The Logistic Regression Model (Model-3) is the emphasis of this project. The Logistic Regression is used to predict the probability of Default on loan based on other independent variables. In this case, the probability of the Default based on the identified required independent and explanatory variables of duration, amount, installment, age (continuous variables), history, purpose, and rent (categorical variables).

A random selection of 900

of the 1000 cases is made for the

Training set, and the remaining of 100 cases is

made into the Test set. The

result shows the coefficient estimates, starting with a negative intercept

(slope) of -2.705e-01 with a standard error of 4.833e-01, and the coefficient for each of these identified

explanatory variables are also estimated.

The standard error of the coefficient estimates represents the accuracy

of the coefficient. The larger the standard error, the less confident about the

estimates. The (z) value represents the z-statistic, which is the coefficient estimate

divided by the standard error of the estimates.

The Pr(>|z|) is the last column in the result of the logistic

analysis, where the p-value corresponding to the z-statistic. The smaller the p-value, the more significant

the estimates are. One unit increase in duration (an increase in

the number of duration by one) is associated

with an increase of logarithm of the odds of the observation being

Default. As indicated in (Fischetti et al., 2017), if the

coefficient is positive, it has a positive impact on the probability of the

dependent variable, and if the coefficient is negative, it has a negative

impact on the probability of the binary outcome (Default). The age, history with poor and terrible, the purpose for used care, goods or repairs,

education, and business, have negative coefficient values indicating that there is

a negative impact on the probability of the binary outcome of the Default. The duration, amount, installment and rent

show positive coefficient values

indicating that they have a positive impact on the probability of the dependent binary outcome (Default). As the p-value is much less than 0.05 for

duration, amount, installment, history, purpose for used car, goods, repair,

and business, and rent, we reject the null hypotheses that there is no significance of the parameter to the model and

accept the alternate hypotheses that there is significance of the parameter to

the model. The p-value for the age is

(p=0.05) indicating that we accept the null hypothesis that there is no significance of the parameter to the

model. The p-value for (purpose) of education is > 0.05

indicating that we accept the null hypothesis that there is no significance of the parameter to the model. The performance of the Logistic Regression

model for the Test dataset shows that the

Logistic Regression recognizes 23 of the 28 Defaults (82%) and predicts the

defaults 42 of the 72 good loans (58%).

The coordinates of the sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity = 0.82,

1-specifictiy=0.58) define one point on the ROC curve (Figure 18). The sensitivity = 8/28=0.29, and specificity

=68/72=0.94 for another point on ROC curve (sensitivity = 0.29,

1-specificity=0.06) (Figure 19). The ROC

is calculated using various cutoff on the probability. The ROC curves that assess the predictive

quality of the classification rule on the holdout sample of 100 observations as

shown in (Figure 18), and on the complete data set of all 1000 cases as shown

in (Figure 19). Specified values on

sensitivity and specificity imply a

certain value for the probability cutoff.

However, for certain data and models,

no cutoff may achieve the given desires properties on sensitivity and specificity, implying that the desired sensitivity and specificity

cannot be attained (Ledolter, 2013).

References

Ahlemeyer-Stubbe, A., & Coleman, S. (2014). A practical guide to data mining for business and industry: John Wiley & Sons.

Bommae, K. (2015). Understanding Diagnostic Plots of Linear Regression Analysis. Retrieved from https://data.library.virginia.edu/diagnostic-plots/.

Fischetti, T., Mayor, E., & Forte, R. M. (2017). R: Predictive Analysis: Packt Publishing.

Hodeghatta, U. R., & Nayak, U. (2016). Business Analytics Using R-A Practical Approach: Springer.

Ledolter, J. (2013). Data mining and business analytics with R: John Wiley & Sons.

Navarro, D. J. (2015). Learning statistics with R: A tutorial for psychology students and other beginners. R package version 0.5.

r-project.org. (2018). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf.