Dr. O. Aly

Computer Science

Introduction: The purpose of this discussion is to discuss the issues of overfitting versus using parsimony and their importance in Big Data analysis. The discussion also addresses if the overfitting approach is a problem in the General Least Square Model (GLM) approach. Some hierarchical methods which do not require parsimony of GLM are also discussed in this discussion. This discussion does not include the GLM as it was discussed earlier. It begins with Parsimony in Statistics model.

Parsimony Principle in Statistical Model

The medieval (14th century) English philosopher, William of Ockham (1285 – 1347/49) (Forster, 1998) popularized a critical principle stated by Aristotle “Entities must not be multiplied beyond what is necessary” (Bordens & Abbott, 2008; Epstein, 1984; Forster, 1998). The refinement of this principle by Ockham is now called “Occam’s Razor” stating that a problem should be stated in the simplest possible terms and explained with the fewest postulates possible (Bordens & Abbott, 2008; Epstein, 1984; Field, 2013; Forster, 1998). This method is now known as Law or Principle of Parsimony (Bordens & Abbott, 2008; Epstein, 1984; Field, 2013; Forster, 1998). Thus, based on this law, a theory should account for phenomena within its domain in the simplest terms possible and with the fewest assumptions (Bordens & Abbott, 2008; Epstein, 1984; Field, 2013; Forster, 1998). As indicated by (Bordens & Abbott, 2008), if there are two competing theories concerning a behavior, the one which explains the behavior in the simplest terms is preferred under the law of parsimony.

Modern theories of the attribution process, development, memory, and motivation adhere to this law of parsimony (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). However, the history of science witnessed some theories which got crushed under their weight of complexity (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). For instance, the collapse of interest in the Hull-Spence model of learning occurred primarily because the theory had been modified so many times to account for anomalous data that was no longer parsimonious (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). The model of Hull-Spence became too complicated with too many assumptions and too many variables whose values had to be extracted from the very data that the theory was meant to explain (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). As a result of such complexity, the interest in the theory collapsed and got lost. The Ptolemaic Theory of planetary motion also lost its parsimony because it lost much of its true predictive power (Bordens & Abbott, 2008).

Parsimonious is one of the characteristics of a good theory (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). Parsimonious explanation or a theory explains a relationship using relatively few assumptions (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). When more than one explanation is offered for observed behavior, scientists and researchers prefer the parsimonious explanation which explains behavior with the fewest number of assumptions (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). Scientific explanations are regularly evaluated and examined for consistency with the evidence and with known principles for parsimony and generality (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). Accepted explanations can be overthrown in favor of views which are more general, more parsimonious, and more consistent with observation (Bordens & Abbott, 2008).

How to Develop Fit Model Using Parsimony Principle

When building a model, the researcher should strive for parsimony (Bordens & Abbott, 2008; Field, 2013). The statistical implication of using a parsimony heuristic is that models be kept as simple as possible, meaning predictors should not be included unless they have the explanatory benefit (Field, 2013). This strategy can be implemented by fitting the model that include all potential predictors, and then systematically removing any that do not seem to contribute to the model (Field, 2013). Moreover, if the model includes interaction terms, then, the interaction terms to be valid, the main effects involved in the interaction term should be retained (Field, 2013). Example of the implementation of Parsimony in developing a model include three variables in a patient dataset: (1) outcome variable (as cured or not cured), which is dependent variable (DV), (2) intervention variable, which is a predictor independent variable (IV), and (3) duration, which is another predictor independent variable (Field, 2013). Thus, the three potential predictors can be Intervention, Duration and the interaction of the “Intervention x Duration” (Field, 2013). The most complex model includes all of these three predictors. As the model is being developed, any terms that are added but did not improve the model should be removed and adopt the model which did not include those terms that did not make a difference. Thus, the first model (model-1) which the researchers can fit would be to have only Intervention as a predictor (Field, 2013). Then, the model is built up by adding in another main effect of the Duration in this example as model-2. The interaction of the Intervention x Duration can be added in model-3. Figure 1 illustrates these three models of development. The goal is to determine which of these models best fits the data while adhering to the general idea of parsimony (Field, 2013). If the interaction term model-3 did not improve the model (model-2), then model-2 should be used as the final model. If the Duration in model-2 did not make any difference and did not improve model-1, then model-1 should be used as the final model (Field, 2013). The aim is to build the model systematically and choose the most parsimonious model as the final model. The parsimonious representations are essential because simpler models tend to give more insight into a problem (Ledolter, 2013).

Figure 1. Building Models based on the Principle of Parsimony (Field, 2013).

Overfitting in Statistical Models

Overfitting is a term used when using models or procedures which violate Parsimony Principle, it means that the model includes more terms than are necessary or uses more complicated approaches than necessary (Hawkins, 2004). There are two types of “Overfitting” methods. The first “Overfitting” method is to use a model which is more flexible than it needs to be (Hawkins, 2004). For instance, a neural net can accommodate some curvilinear relationships and so is more flexible than a simple linear regression (Hawkins, 2004). However, if it is used on a dataset that conforms to the linear model, it will add a level of complexity without any corresponding benefit in performance, or even worse, with poorer performance than the simpler model (Hawkins, 2004). The second “Overfitting” method is to use a model that includes irrelevant components such as a polynomial of excessive degree or a multiple linear regression that has irrelevant as well as the needed predictors (Hawkins, 2004).

The “Overfitting” technique is not preferred for four essential reasons (Hawkins, 2004). The first reason involves wasting resources and expanding the possibilities for undetected errors in databases which can lead to prediction mistakes, as the values of these unuseful predictors must be substituted in the future use of the mode (Hawkins, 2004). The second reason is that the model with unneeded predictors can lead to worse decisions (Hawkins, 2004). The third reason is that irrelevant predictor can make predictions worse because the coefficients fitted to them add random variation to the subsequent predictions (Hawkins, 2004). The last reason is that the choice of model has an impact on its portability (Hawkins, 2004). The one-predictor linear regression that captures a relationship with the model is highly portable (Hawkins, 2004). The more portable model is preferred over, the less portable model, as the fundamental requirement of science is that one researcher’s results can be duplicated by another researcher (Hawkins, 2004).

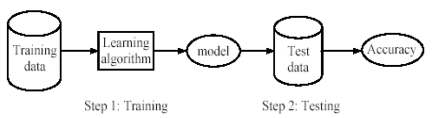

Moreover, large models overfitted on training dataset turn out to be extremely poor predictors in new situations as needed predictor variables increase the prediction error variance (Ledolter, 2013). The overparameterized models are of little use if it is difficult to collect data on predictor variables in the future. The partitioning of the data into training and evaluation (test) datasets is central to most data mining methods (Ledolter, 2013). Researchers must check whether the relationships found in the training dataset will hold up in the future (Ledolter, 2013).

How to recognize and avoid Overfit Models

A model overfits if it is more complicated than another model that fits equally well (Hawkins, 2004). The recognition of overfitting model involves not only the comparison of the simpler model and the more complex model but also the issue of how the fit of a model is measured (Hawkins, 2004). Cross-Validation can detect overfit models by determining how well the model generalizes to other datasets by partitioning the data (minitab.com, 2015). This process of cross-validation helps assess how well the model fits new observations which were not used in the model estimation process (minitab.com, 2015).

Hierarchical Methods

The regression analysis types include simple, hierarchical, and stepwise analysis (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). The main difference between these types is how predictor variables are entered into the regression equation which may affect the regression solution (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). In the simple regression analysis, all predictors variables are entered together, while in the hierarchical regression, the order in which variables are entered into the regression equation is specified (Bordens & Abbott, 2008; Field, 2013). Thus, the hierarchical regression is used for a well-developed theory or model suggesting a specific causal order (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). As a general rule, known predictors should be entered into the model first in order of their importance in predicting the outcome (Field, 2013). After the known predictors have been entered, any new predictors can be added into the model (Field, 2013). In the stepwise regression, the order in which variables are entered is based on a statistical decision, not on a theory (Bordens & Abbott, 2008).

The choice of the regression analysis should be based on the research questions or the underlying theory (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). If the theoretical model is suggesting a particular order of entry, the hierarchical regression should be used (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). Stepwise regression is infrequently used because sampling and measurement error tends to make unstable correlations among variables in stepwise regression (Bordens & Abbott, 2008). The main problem with the stepwise methods is that they assess the fit of a variable based on the other variables in the model (Field, 2013).

Goodness-of-fit Measure for the Fit Model

Comparison between hierarchical and stepwise methods: The hierarchical and stepwise methods involve adding predictors to the model in stages, and it is useful to know these additions improve the model (Field, 2013). Since the larger values of R2 indicates better fit, thus, a simple way to see whether a model has improved as a result of adding predictors to it would be to see whether R2 for the new model is bigger than for the old model. However, it will always get bigger if predictors are added, so the issue is more whether it gets significantly bigger (Field, 2013). The significance of the change in R2 can be assessed using the equation below as the F-statistics is also be used to calculate the significance of R2 (Field, 2013)

However, because the focus is on the change in the models, thus the change in R2 (R2 change) and R2 of the newer model (R2 new) are used using the following equation (Field, 2013). Thus, models can be compared using this F-ratio (Field, 2013).

The Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) method is a goodness-of-fit measure which penalizes the model for having more variables. If the AIC is bigger, the fit is worse; if the AIC is smaller, the fit is better (Field, 2013). If the Automated Linear Model function in SPSS is used, then AIC is used to select models rather than the change in R2. AIC is used to compare it with other models with the same outcome variables; if it is getting smaller, then the fit of the model is improving (Field, 2013). In addition to the AIC method, there is Hurvich and Tsai’s criterion (AICC), which is a version of AIC designed for small samples (Field, 2013). Bozdogan’s criterion (CAIC), which is a version of AIC which is used for model complexity and sample size. Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) of Schwarz, which is comparable to the AIC (Field, 2013; Forster, 1998). However, it is slightly more conservative as it corrects more harshly for the number of parameters being estimated (Field, 2013). It should be used when sample sizes are large, and the number of parameters is small (Field, 2013).

The AIC and BIC are the most commonly used measures for the fit of the model. The values of these measures are all useful as a way of comparing models (Field, 2013). The value of AIC, AICC, CAIC, and BIC can all be compared to their equivalent values in other models. In all cases, smaller values mean better-fitting models (Field, 2013).

There is also Minimum Description Length (MDL) measure of Rissanen, which is based on the idea that statistical inference centers around capturing regularity in data; regularity, in turn, can be exploited to compress the data (Field, 2013; Vandekerckhove, Matzke, & Wagenmakers, 2015). Thus, the goal is to find the model which compresses the data the most (Vandekerckhove et al., 2015). There are three versions of MDL: crude two-part code, where the penalty for complex models is that they take many bits to describe, increasing the summed code length. In this version, it can be difficult to define the number of bits required to describe the model. The second version of MDL is the Fisher Information approximation (FIA), which is similar to AIC and BIC in that it includes a first term that represents goodness-fo-fit, and additional terms that represent a penalty for complexity (Vandekerckhove et al., 2015). The second term resembles that of BIC, and the third term reflects a more sophisticated penalty which represents the number of distinguishable probability distribution that a model can generate (Vandekerckhove et al., 2015). The FIA differs from AIC and BIC in that it also accounts for functional form complexity, not just complexity due to the number of free parameters (Vandekerckhove et al., 2015). The third version of MDL is normalized maximum likelihood (NML) which is simple to state but can be difficult to compute, for instance, the denominator may be infinite, and this requires further measures to be taken (Vandekerckhove et al., 2015). Moreover, NML requires integration over the entire set of possible datasets, which may be difficult to define as it depends on unknown decision process in the researchers (Vandekerckhove et al., 2015).

AIC and BIC in R: If there are (p) potential predictors, then there are 2p possible models (r-project.org, 2002). AIC and BIC can be used in R as selection criteria for linear regression models as well as for other types of models. As indicated in (r-project.org, 2002): the equations for AIC and BIC are as follows.

For the linear regression models, the -2log-likelihood (known as the deviance is nlog(RSS/n)) (r-project.org, 2002). AIC and BIC need to get minimized (r-project.org, 2002). The Larger models will fit better and so have smaller RSS but use more parameters (r-project.org, 2002). Thus, the best choice of model will balance fit with model size (r-project.org, 2002). The BIC penalizes larger models more heavily and so will tend to prefer smaller models in comparison to AIC (r-project.org, 2002).

Example of the code in R using the state.x77 dataset is below. The function does not evaluate the AIC for all possible models but uses a search method that compares models sequentially as shown in the result of the R commands.

- g <- lm(Life.Exp ~ ., data=state.x77.df)

- step(g)

References

Bordens, K. S., & Abbott, B. B. (2008). Research Design and Methods: A Process Approach: McGraw-Hill.

Epstein, R. (1984). The principle of parsimony and some applications in psychology. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 119-130.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics: Sage publications.

Forster, M. R. (1998). Parsimony and Simplicity. Retrieved from http://philosophy.wisc.edu/forster/220/simplicity.html, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Hawkins, D. M. (2004). The problem of overfitting. Journal of chemical information and computer sciences, 44(1), 1-12.

Ledolter, J. (2013). Data mining and business analytics with R: John Wiley & Sons.

minitab.com. (2015). The Danger of Overfitting Regression Models. Retrieved from http://blog.minitab.com/blog/adventures-in-statistics-2/the-danger-of-overfitting-regression-models.

r-project.org. (2002). Practical Regression and ANOVA Using R Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/doc/contrib/Faraway-PRA.pdf.

Vandekerckhove, J., Matzke, D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2015). Model Comparison and the Principle The Oxford handbook of computational and mathematical psychology (Vol. 300): Oxford Library of Psychology.