Dr. Aly, O.

Computer Science

Abstract

The purpose of this project is to discuss and analyze scalable and intelligent security analytics tools from different vendors. The discussion begins with an overview of SIEM and the essential capabilities of an analytics-driven SIEM. The first generation of SIEM has been overwhelmed with the volume of the data and the rise of the advanced threats. The second generation of SIEM was introduced because Big Data tools have the potential to provide significant enhancement in the action of the security intelligence by minimizing the time for correlating, consolidating, and contextualizing diverse security event information and also for correlating long-term historical data for forensic purposes. The discussion and the analysis are limited to only four scalable and intelligent security analytics; AlienVault, QRadar, Splunk, and LogRhythm. The Unified Security Management (USM) of AlienVault includes SIEM, vulnerability assessment, asset discovery, flow and packet capture, network and host detection, and file integrity monitoring. The USM is utilized to improve the security visibility throughout the organization and to detect security incidents in the real-time. IBM Security QRadar provides management for log and events, behavioral and reporting analysis for the network and applications. Splunk Enterprise Security enables the search of the data and the implementation of visual correlation to identify malicious events and collect data about the context of those events. LogRhythm supports log management and has the capabilities of the network forensic. They can be deployed in smaller environments. The discussion and the analysis include the key design considerations for scalability of each tool. The project also discusses the advantages and the disadvantages of these four intelligent security analytic tools.

Keywords: SIEM, Security Analytics Tools, QRadar, AlienVault, LogRhythm, Splunk.

Introduction

The advanced threats which often called advanced persistent threats or APTs are the primary reason which drives the organization to collect and analyze information. The APTs are sophisticated attacks (Oprea, Li, Yen, Chin, & Alrwais, 2015), and can involve multiple events occurring across the organization which would otherwise not be connected without the utilization of advanced intelligence (SANS, 2013). APTs cause severe risks and damages to organizations and governments because they target the confidential propriety information (SANS, 2013).

Advanced threats require advanced intelligent and analytic tools. Recent years have witnessed the rise of more sophisticated attacks including the APTs (IBM, 2013; Oprea et al., 2015; SANS, 2013). In a survey conducted by (SANS, 2013), the APTs affected two-thirds of the respondents in the past two years. The result showed that one respondent is seeing almost 500 attacks in a nine-month period, and many seeing somewhere between one and twenty. Thus, the number of the APTs is increasing. As indicated in (Radford, 2014) “Frequently, a victim of these attacks [APTs] do not even know that their perimeter security has been penetrated for an average of 243 days. They all have up-to-date anti-virus software, and 100% of breaches involve stolen credentials.” The APTs is in every organization’s mind (Radford, 2014). The Cloud Service Providers (CSP) is the prime target for cyber-attacks. Organizations who utilize the Cloud technology must consider the myriad access points to their data when hosted in a Cloud environment and should consider at length the solutions available to them, and pertinently that all data access points are covered (Radford, 2014). The PAT is one of various security threats against which organizations must protect their information.

Various security techniques are offered to deal with security threats including the APTs. This project discusses and analyzes four scalable and intelligent security tools from different vendors. The analysis covers the main functions such as anomaly detection capability, event correlation capability, real-time analytics capability, and so forth of each tool. The analysis includes an assessment if the tool is suited or used in the Cloud Computing, and an identification of the targeted applications. The analysis also includes the pros and cons of each tool. The project begins with an overview of Security Information and Event Management, followed by the scalable and intelligent security tools from different vendors.

Security Information and Event Management (SIEM)

The traditional and conventional model for protecting the data often focused on network-centric and perimeter security, using devices such as firewalls and intrusion detection systems (Oprea et al., 2015; Shamsolmoali & Zareapoor, 2016). However, this conventional approach is not adequate when dealing with Big Data and Cloud Computing technologies. The conventional approach does not provide enough protection against the advanced persistent threats (APT), privileged users or any other malicious security attacks (Oltsik, 2013; Oprea et al., 2015; Shamsolmoali & Zareapoor, 2016).

Thus, many organizations deploy other techniques such as the database audit and protection (DAP), and security information and event management (SIEM) to collect information about the network activities (Shamsolmoali & Zareapoor, 2016). Examples of the SIEM techniques include RSA envision and HP ArchSight using a standardized approach to collecting information and events, storing and querying and providing correlation degrees driven by rules (Pearson, 2013). However, SIEM provides inputs which need to be properly analyzed and translated into a certain format to be utilized by senior risk evaluators and strategic policymakers. This manual process is not adequate when dealing with security issues. Moreover, the standards of the risk assessment such as ISO2700x and NIST operate at a macro-level and usually do not fully leverage information coming from logging and auditing activities carried out by the IT operations (Pearson, 2013). Thus, SIEM lacks a solution for the business audit and strategic risk assessment (Pearson, 2013).

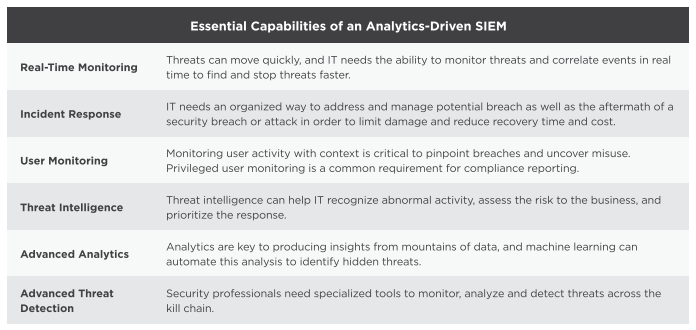

In (Splunk, 2017), SIEM which is analytic-driven has six essential capabilities, (1) Real-Time Monitoring, (2) Incident Response, (3) User Monitoring, (4) Threat Intelligence, (5) Advanced Analytics, and (6) Advanced Threat Detection. Table 1 summarizes these six essential capabilities of an analytics-driven SIEM (Splunk, 2017).

Table 1. Six Essential Capabilities of an Analytics-Driven SIEM. Adapted from (Splunk, 2017).

In a survey implemented by (SANS, 2013), the result showed 58% of the respondents were using dedicated log management and 37% were using a SIEM system. The result also showed that nearly half of the respondents have dedicated log management platforms, SIEM, and scripted searches a part of their data collection and analysis processes. The result showed that less than 10% utilizes unstructured data repositories and specific Big Data framework for analysis and search. Figure 1 illustrates the types of Security Data Analysis Tools in Use.

Figure 1. Types of Security Data Analysis Tool in Use. Adapted from (SANS, 2013).

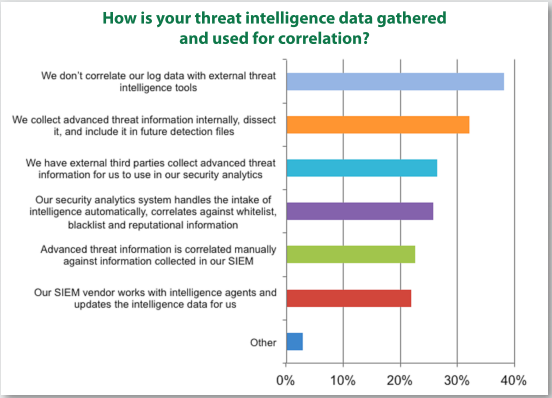

As indicated in (SANS, 2013), the dedicated log management platform does not meet the needs created by Big Data collection. SIEM is anticipated to step up and meet the needs created by Big Data collection (SANS, 2013). The survey results also showed that 26% of the respondents rely on analytics tools to do the heavy lifting of threat intelligence, and others leverage SIEM platforms and manual techniques as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Threat Intelligence Capabilities. Adapted from (SANS, 2013).

In the same survey, the result showed that 51% of the respondents indicated they are currently using third-party intelligence services as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The Use of Third Party Intelligence Tools. Adapted from (SANS, 2013).

The result of the survey also showed that the most organizations are still focused on the fundamentals such as better SIEM, more training to detect patterns of malicious activity, vulnerability management, and network protection tools, and endpoints visibility for future investments in security analytics and Big Data platform as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Future Investments in Analytics/Intelligence. Adapted from (SANS, 2013).

Scalable and Intelligent Security Analytic Tools

The management of alerts from different intrusion detection sensors and rules was a big challenge in the settings of the organizations. The first generation of SIEM was able to aggregate and filter alarms from many sources and present actionable information to security analysis (CSA, 2013). However, the first generation of SIEM has been overwhelmed with the volume of the data (Glick, 2014), and cannot keep up with the rate and complexity of the current wave of the cyber attacks and advanced threats (Splunk, 2017). The second generation of SIEM was introduced because Big Data tools have the potential to provide a significant enhancement in the action of the security intelligence by minimizing the time for correlating, consolidating, and contextualizing diverse security event information, and also for correlating long-term historical data for forensic purposes (CSA, 2013).

Most of the current SIEM systems provide the same basic features, except for those features proposed by vendors. However, the basic feature of the SIEM systems contains Server, Database, FrontEnd, Probes, and Agents (Di Mauro & Di Sarno, 2018). The Server is the core component of the whole deployment for collecting and processing the log coming from the external sources on behalf of the correlation engine. The Database stores the data for analysis and runtime configuration of SIEM. The FrontEnd is the user interface to the Server, while the Probe is the collection of sensors deployed within the monitored infrastructure. The typical examples of the Probes include perimeter defense systems such as firewalls and intrusion prevention systems, host sensors such as Host IDSs, or security applications such as web firewalls and authentication systems (Di Mauro & Di Sarno, 2018). The Agent represents the counterparts of probes embedded in the server and can convert heterogenous logs generated by different probes, in logs with the same syntax and a specific semantic (Di Mauro & Di Sarno, 2018). Figure 5 illustrates the classical framework of the SIEM systems.

Figure 5. A Classical Framework of a SIEM System. Adapted from (Di Mauro & Di Sarno, 2018).

The security analytics market is rapidly evolving as vendors are merging, developers are adding new features, and tools once deployed exclusively on-premises which are also offered as a Cloud service (Dan Sullivan, 2015). As indicated in (Dan Sullivan, 2015), there are three reasons for organizations to deploy security analytics software. These reasons are the compliance, security event detection and remediation, and forensics. The compliance is regarded to be the key driver of security requirement for more organizations. It is imperative to verify the compliance because the government and industry regulations, organizations implement their security policies and procedures (Dan Sullivan, 2015). The security analytics tools should alert organizations to significant events which are defined by rules such as trigger (Dan Sullivan, 2015). The tools can help in minimizing the time and effort required to collect, filter, and analyze event data (Dan Sullivan, 2015). The attacks can occur at high speed; these tools should also be at high speed to detect the malicious attacks. In case the attack took place, the organization should be able to block any future attacks through the forensics, as the forensic analysis can reveal vulnerabilities in the network of the organization or desktop security controls which were not known prior the attack (Dan Sullivan, 2015).

Thus, organizations must consider deploying security analytics software. Various security analytics tools are introduced with the aim to detect and block any malicious attacks. Examples of these security analytics tools include AlienVault, QRadar, Splunk, LogRhythm, FireEye, McAfee Enterprise Security Manager, and so forth. This project discusses and analyzes four of these security analytic tools, their features, the pros, and cons.

- AlienVault

AlienVault started in 2007. During 2010 the company received an initial round of venture capital funding and relocated the headquarters from Spain to United States (Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011). The AlienVault’s Unified Security Management (USM) provides SIEM, vulnerability assessment, network and host intrusion detection, file integrity monitoring functions via software or appliance options (Mello, 2016; Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011), asset discovery, and the capture of the flow and packets (Mello, 2016). The AlienVault Unified SIEM contains the proprietary and the Open Source Security Information Management (OSSIM). OSSIM has been available since 2003 and is an open source security management platform. AlienVault integrates OSSIM into the SIEM solution to offer enhanced performance, consolidated reporting and administration, and multi-tenanting for most managed security service providers (Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011). AlienVault added the real-time feature in 2010. AlienVault’s long-term plan features to solve existing competitive gaps in areas such as application, monitoring feature for data and users, while the short-term plan includes dynamic monitor system to rule-based correlation (Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011).

AlienVault’s USM offers three major advantages. AlienVault offers SIEM solution, monitoring system for file integrity, assessment system for vulnerability, control for the endpoint, and intrusion detection system. AlienVault is based on open source. It is regarded to be less expensive than the corresponding product sets from most competitors in the SIEM domain (Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011). A more recent review of AlienVault Unified SIEM by (Vanhees, 2018), indicates that the AlienVault Unified Security System incorporates various technologies such as vulnerability scanning, NetFlow, host intrusion detection system, and network intrusion detection system. Moreover, it is easy to scale up and down, and it scores very high in that aspect (Vanhees, 2018). In another review by (Morrissey, 2015), AlienVault can identify risks and vulnerabilities on systems, to provide log consolidation and analysis, and to correlate threats between different systems. As cited in (Mello, 2016), Gartner recommends AlienVault’ USM for organizations which require a broad set of integrated security capabilities, either on-premises or in AWS environment.

AlienVault has disadvantages and limitations. AlienVault lacks support for Database Activity Monitoring (DAM). Moreover, there is no feature to integrate third-party DAM technologies (Mello, 2016; Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011). AlienVault lack supports the integration of Identity and Access Management (IAM) beyond Active Directory Monitoring (Mello, 2016; Nicolett & Kavanagh, 2011). Report on AlienVault Unified Security Management by (Morrissey, 2015; Vanhees, 2018) indicates that it is not easy to develop custom plugins compared to other products, and to setup correlation rules. Moreover, it is difficult to deal with static data as it deals only with dynamic data like syslogs, NetFlow, data captures, and so forth. The custom reporting is very limited, and the task of creating a bar chart to visualize most common attacked ports is not possible. Organizations which requires high-end reporting, advanced correlation rules or complex use case scenarios, should not consider AlienVault (Vanhees, 2018).

Although AlienVault’s USM has this limitation, in a review by (Vanhees, 2018), AlienVault’s USM is described as a “huge value” as it does not require any additional setup and is baked into the tool nicely and smoothly compared with other vendors. It helps detect suspicious traffic (Morrissey, 2015; Vanhees, 2018), and it automatically syncs with other intelligence feeds which are regarded to be handy. The correlation rules are used to spot unwanted behavior proactively (Vanhees, 2018).

- QRadar

QRadar is IBM’s SIEM platform (Mello, 2016). It is composed of QRadara Log Manager, Data Node SIEM, Risk Manager, Vulnerability Manager, QFlow, and VFlow Collectors, and Incident Forensics (Mello, 2016). It uses the capabilities of Big Data to keep up with the advanced threats and prevent attacks before they occur (IBM, 2013). QRadar has the capabilities to reveal hidden relationships within massive amount of security data using proven analytics to minimize billions of security events to a manageable set of prioritized incidents (IBM, 2013).

The platform of IBM Security QRadar can be deployed as a physical or virtual or as a cloud service solution (Mello, 2016). It can be installed using various options such as “all-in-one” implementation option or scaled. QRadar provides capabilities such as collection and processing of the event and log data, NetFlow, deep-packet inspection of network traffic, and full-packet capture and behavior analysis (McKelvey, Curran, Gordon, Devlin, & Johnston, 2015; Mello, 2016). IBM added more enhanced features to QRadar to support IBM X-Force Exchange for sharing threat intelligence and IBM Security App Exchange for sharing applications, and security app extensions (Mello, 2016). After the acquisition of Resilient Systems in 2016 (Rowinski, 2016), IBM developed an integrated end-to-end security operations and response platform offering a quick response to cyber incidents. It also enhanced the multi-tenant feature, and the capabilities of the search and system administration (Mello, 2016).

The IBM’s QRadar utilizes a distributed data management system providing horizontal scaling of data storage (D. Sullivan, 2016). While organizations can utilize distributed USIM to access local data in some cases, they may also require searching across the distributed platform in some other scenarios. QRadar incorporates a search engine which enables searching locally as well as across platforms (D. Sullivan, 2016). QRadar is a big data SIEM utilizing data nodes instead of storage area network (SAN), which help in reducing the associated cost and the complexity of the management (D. Sullivan, 2016). QRadar is a distributed storage model based on data nodes and can scale to petabytes of storage and can meet the requirement of organizations for a large volume of long-term storage (D. Sullivan, 2016). QRadar has a vulnerability management component which is designed to integrate data from various vulnerability scanners and enhance that data with context-relevant information about network usage (D. Sullivan, 2016). It has been used to process a large volume of events per second in real-world applications (D. Sullivan, 2016). QRadar can be deployed in the Cloud to reduce the infrastructure management (D. Sullivan, 2016)). The Security QRadar Risk Manager add-on offers the capability of the automated monitoring, provides support for multiple vendor product audits, and assessment of compliance policy, and threat modeling (D. Sullivan, 2016). QRadar platform can meet the requirement of mid-size and large organization with general SIEM needs. It is also a good fit for mid-size organizations which require a solution with flexible implementation, hosting, and monitoring options. QRadar is also good for organizations which look for a single security event and response platform for their security operation centers (Mello, 2016). In recent reviews by (Verified-User2, 2017), IBM QRadar was the preferred option for the clients of the organizations across all departments for fast deployment and instant log visibility to meet security and compliance requirements.

QRadar has various areas of strength and advantages. It provides an integrated view of log and event data and the correlation of network traffic behavior across NetFlow and event logs. It also supports security event and monitoring feature for the log in IaaS Cloud Service Model, including the monitoring for AWS CloudTrail and SoftLayer (Mello, 2016). The security platform of QRadar is straightforward to implement and maintain (Mello, 2016). In more recent reviews of IBM QRadar by (Verified-User2, 2017), IBB QRadar was described as simple, flexible framework, easy deployment and out of the box content good enough to have quick wins. In another review by (Verified-User1, 2017), the creation of rules is intuitive and fast helping in emergency scenarios. The maintenance of IBM QRadar is light, and the appliance has nearly flawless uptime (Verified-User1, 2017). The generation of the reports is very functional and efficient (Verified-User1, 2017). It was described as a positive return on investment in a recent review by (Verified-User2, 2017). Moreover, third-party capabilities can be plugged into the framework through the Security App Exchange (Mello, 2016). This capability of third-party support is useful because QRadar has limitation for the endpoint monitoring for threat detection and response and the integrity of the basic file (Mello, 2016).

QRadar has additional limitations besides the endpoint monitoring. In recent reviews by (Verified-User1, 2017), the limitations of IBM QRadar includes the steep learning curve compared to other platforms. QRadar does require training and homework. Moreover, there is a lack of threat feed utilization of STIX (Structured Threat Information Expression)/TAXII (Trusted Automated Exchange of Indicator Information), which remains very limited (Verified-User1, 2017). It may require a considerable amount of tuning during the deployment with very little “out of the box” offense information (Verified-User1, 2017). In another recent review by (Verified-User2, 2017), IBM QRadar is limited in event log parsing, and the correlation engine needs to be more flexible and dynamic (Verified-User2, 2017).

- Splunk

The Splunk Enterprise (SE) is the core product of the company (Mello, 2016). It provides log and event collection, searches and visualization with the query language of Splunk (Mello, 2016). The Splunk Enterprise Security (SES) provides security features including correlation rules, reports and pre-defined dashboards (Mello, 2016). SES supports the real-time monitoring and alerts, incident response and compliance reporting (Mello, 2016). SE and SES can be deployed locally on-premise, or in public, private or hybrid Cloud, or as a service using the Cloud Service Models (Mello, 2016). Splunk acquired Caspida in 2015 (Mello, 2016; Tinsley, 2015). After the acquisition, Splunk added the native behavioral analytics to its repertoire (Mello, 2016). Moreover, it provided support to third-party UEBA products (Mello, 2016). Additional features have been added to SES to integrate with other behavioral products. More capabilities such as improved incident management and workflow capabilities, lower data storage requirements, better visualizations have been implemented. The expansion of monitoring system to additional infrastructure and software-as-a-service provider (Mello, 2016).

Splunk has the capabilities of broad data ingestion, offering connectors to the data sources and allowing custom connectors (D. Sullivan, 2016). Splunk systems stores data in the schema-less database and uses indexes based on ingestion enabling various data types with rapid query response (D. Sullivan, 2016). Splunk provides flexible SIEM platform which can handle various data sources and has the analytic capabilities or a single data analysis platform (Mello, 2016). Splunk was found gaining “significant” visibility across the client base of Gartner (Mello, 2016). Splunk has strong advanced security analytics for combating advanced threat detection and insider threats (Mello, 2016).

Splunk has various advantages. In a review by (Taitingfong, 2015), Splunk was found to be flexible and extensible. It can ingest logs from disparate systems using disparate formats and disparate file types (Murke, 2015; Taitingfong, 2015). Splunk was found to be flexible in parsing, formatting, and enhancing the data (Taitingfong, 2015). Splunk was found to scale very well in large environments adding more indexers as needed with the expanded environment (Kasliwal, 2015; Murke, 2015; Taitingfong, 2015). Splunk can do multi-site clustering and search head clustering providing load balancing and redundancy (Taitingfong, 2015). In another review by (Murke, 2015), Splunk has the capability of the real-time analysis. Splunk provided the best results amongst its competitors as indicated in the review of (Murke, 2015). It provided fast results on large datasets and is easy to manage as indicated in the review by (Murke, 2015).

Splunk system has limitations. SES product provides only the basic pre-defined correlations for user monitoring and reporting (Mello, 2016). The licensing model for high volume data costs more than other SIEM products, although Splunk offers a new licensing scheme for high-volume data users (Mello, 2016). In recent reviews by (Kasliwal, 2015; Taitingfong, 2015), the search language of Splunk, the more advanced formatting or statistical analysis were found very deep and required a learning curve. The dashboard of Splunk may require more visualization which requires development using simple XML, Java Scripts and CSS (Taitingfong, 2015). Moreover, Splunk releases minor revisions very quickly due to the increased number of bugs (Taitingfong, 2015). In another review by (Murke, 2015), Splunk was found limited in providing optimized results with the smaller size of data. Moreover, it was found by (Kasliwal, 2015; Murke, 2015) as costly.

- LogRhythm

The SIEM of the LogRhythm supports n-tier-scalable, decentralized architecture (Mello, 2016). LogRhythm’s SIEM is composed of various tools such as Platform Manager, AI Engine, Data Processors, Data Indexers, and Data Collectors (Mello, 2016). The deployment of LogRhythm can be consolidated as an all-in-one. The implementation options can be appliance, software or virtual instance format (Mello, 2016). The behavioral analytics of the user and entity, an integrated incident response workflow and automated response capabilities can be combined with other capabilities such as event, endpoint and network monitoring (Mello, 2016). The log processing and indexing capabilities of the LogRhythm’s SIEM are divided into two components of the systems. Moreover, more features to the system are added such as the capabilities of the unstructured search through a new storage backend based on Elasticsearch (Mello, 2016). More features are added such as the clustered full data replication; more parsers for applications and protocols, an improved risk-based prioritization (RBP), support for the Cloud services such as AWS, Box, and Okta. The integration with the Cloud Access Security Broker solutions such as Microsoft’s Cloud App Security and Zscaler are also added to enhance the LogRhythm’s SIEM system (Mello, 2016).

LogRhythm has various advantages. LogRhythm can integrate the capabilities of the advanced threat monitoring with SIEM (Mello, 2016). It offers effective out-of-the-box content and workflows which can help in the automation process (Mello, 2016). It provides highly interactive and customizable and automated response capabilities for performing actions on remote devices (Mello, 2016). It is praised for offering straightforward SIEM systems implementation and maintenance (Mello, 2016). LogRhythm is also described to be very visible in the SIEM evaluations of the Gartner’s clients (Mello, 2016). In a review for LogRhythm by (Eng, 2016), it was described as a great SIEM which is easy to implement. Building blocks using LogRhythm is intuitive and easy using drag and drop building block technique which can be easily manipulated (Eng, 2016). It offers statistical building blocks with powerful anomaly detection capabilities which are found to be more difficult or not possible in other SIEMs products (Eng, 2016). LogRhythm provides better event classification than any other SIEM products (Eng, 2016). In another review by (Ilbery, 2016), LogRhythm has the capabilities to import log files from hundreds of devices into one, and it is easy to search the database (Ilbery, 2016). It also has the capabilities to send alert messages to the network activities using emails. It provides a good view of the network equipment, traffic, and the servers.

LogRhythm some limitations. More enhancement and improvement are required for the custom report engine included (Mello, 2016). In a review by (Eng, 2016), there is a requirement and need for LogRhythm to provide back-end support for threat intelligence lists. There is a proposal by (Eng, 2016) for log rhythm to replace the code with hash tables to avoid the excessive cost associated with referencing lists in the rule. The reporting of LogRhythm was described by (Eng, 2016) as the worst of all SIEM systems because it is not intuitive and needs improvement. In another review for LogRhythm by (Ilbery, 2016), the upgrade process was described as a not easy process.

Conclusion

This project discussed and analyzed scalable and intelligent security analytics tools from different vendors. The discussion began with an overview of SIEM and the essential capabilities of an analytics-driven SIEM. The first generation of SIEM has been overwhelmed with the volume of the data and the rise of the advanced threats. The second generation of SIEM was introduced because Big Data tools have the potential to provide significant enhancement in the action of the security intelligence by minimizing the time for correlating, consolidating, and contextualizing diverse security event information and also for correlating long-term historical data for forensic purposes.

Examples

of these security analytics tools include AlienVault, QRadar, Splunk, LogRhythm,

FireEye, McAfee Enterprise Security Manager, and so forth. The discussion and the analysis were limited

to only four scalable and intelligent security analytics; AlienVault, QRadar,

Splunk, and LogRhythm. The Unified

Security Management (USM) of AlienVault includes SIEM, vulnerability

assessment, asset discovery, flow and packet capture, network and host

detection, and file integrity monitoring.

The USM is utilized to improve the security visibility throughout the

organization and to detect security incidents in the real-time. IBM Security QRadar provides management for

log and events, behavioral and reporting analysis for the network and

applications. Splunk Enterprise Security

enables the search of the data and the implementation of visual correlation to

identify malicious events and collect data about the context of those events. LogRhythm supports log management and has the

capabilities of the network forensic.

They can be deployed in smaller environments. The discussion and the

analysis included the key design considerations for scalability of each

tool. The project also discussed the advantages

and the disadvantages of these four intelligent security analytic tools.

References

CSA. (2013). Expanded Top Ten Big Data Security and Privacy Challenges. Cloud Security Alliance, Big Data Working Group.

Di Mauro, M., & Di Sarno, C. (2018). Improving SIEM capabilities through an enhanced probe for encrypted Skype traffic detection. Journal of Information Security and Applications, 38, 85-95.

Eng, J. (2016). LogRhythm Review: “So you want to know which SIEM to buy”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/logrhythm-2016-06-08-06-30-33.

Glick, B. (2014). Information Security is a Big Data Issue. Retrieved from http://www.computerweekly.com/feature/Information-security-is-a-bigdata(05.05).

IBM. (2013). Extending Security Intelligence with Big Data Solutions. Retrieved from http://www.ndm.net/siem/pdf/Extending%20security%20intelligence%20with%20big%20data%20solutions.PDF.

Ilbery, S. (2016). User Review: “LogRhythm does what it promises.”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/logrhythm-2016-06-07-13-22-49.

Kasliwal, G. (2015). Splunk Enterprise Review: “Splunk: Dynamic and Fast compliance tool”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/splunk-2015-12-07-15-43-44.

McKelvey, N., Curran, K., Gordon, B., Devlin, E., & Johnston, K. (2015). Cloud Computing and Security in the Future Guide to Security Assurance for Cloud Computing (pp. 95-108): Springer.

Mello, J. P. J. (2016). Gartner Magic Quadrant for SIEM 2016: Not just for compliance anymore. Retrieved from https://techbeacon.com/highlights-gartner-magic-quadrant-siem-2016.

Morrissey, M. (2015). AlienVault USM Review: “Making sense of the logging overload.”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/alienvault-unified-security-management-2015-09-29-23-21-40.

Murke, S. (2015). Splunk Enterprise Review: “For Real-Time Data Analyzing Get Splunk.”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/splunk-2015-12-07-23-21-33.

Nicolett, M., & Kavanagh, K. M. (2011). Magic Quadrant for Security Information and Event Management.

Oltsik, J. (2013). The Big Data Security Analytics Era Is Here.

Oprea, A., Li, Z., Yen, T.-F., Chin, S. H., & Alrwais, S. (2015). Detection of early-stage enterprise infection by mining large-scale log data. Paper presented at the Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN), 2015 45th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on.

Pearson, S. (2013). Privacy, security and trust in cloud computing Privacy and Security for Cloud Computing (pp. 3-42): Springer.

Radford, C. J. (2014). Challenges and Solutions Protecting Data within Amazon Web Services. Network Security, 2014(6), 5-8. doi:10.1016/S1353-4858(14)70058-3

Rowinski, M. (2016). IBM Security Closes Acquisition of Resilient Systems. Retrieved from http://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/49472.wss, IBM News Release.

SANS. (2013). SANS Security Analytic Survey Retrieved from https://www.sans.org/reading-room/whitepapers/analyst/security-analytics-survey-34980, White Paper.

Shamsolmoali, P., & Zareapoor, M. (2016). Data Security Model In Cloud Computing. Proceedings of 2nd International Conference on Computer Science Networks and Information Technology, Held on 27th – 28th Aug 2016, in Montreal, Canada.

Splunk. (2017). The Six Essential Capabilities of an Analytics-Driven SIEM. Retrieved from https://www.splunk.com/en_us/form/the-six-essential-capabilities-of-analytics-driven-siem.html, White Paper.

Sullivan, D. (2015). Three reasons to deploy security analytics software in the enterprise. Retrieved from http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/feature/Three-reasons-to-deploy-security-analytics-software-in-the-enterprise.

Sullivan, D. (2016). Comparing the top big data security analytics tools. Retrieved from http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/feature/Comparing-the-top-big-data-security-analytics-tools.

Taitingfong, K. (2015). Splunk Enterprise Review: “Splunk – the most flexible SIEM tool on the market.”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/splunk-2015-12-01-16-51-52.

Tinsley, K. (2015). Splunk Acquires Caspida. Retrieved from https://www.splunk.com/en_us/newsroom/press-releases/2015/splunk-acquires-caspida.html, Splunk Press Release.

Vanhees, K. (2018). AlienVault USM Review: “Nothing is what it SIEMs”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/alienvault-unified-security-management-2015-09-29-01-55-26.

Verified-User1. (2017). IBM Security QRadar Review: “Qradar – Big League SIEM Solution”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/products/ibm-security-qradar/reviews. Verified-User2. (2017). IBM Security QRadar Review: “IBM QRadar – A go-to SIEM product”. Retrieved from https://www.trustradius.com/reviews/ibm-security-qradar-2017-06-21-04-06-13, Trust Radius Reviews.